TikTok Audio, Recency Bias And Memefied Misinfo: What's Driving Voters in 2024

Elections researcher Ever Mack breaks down disinformation's viral spiral and how the most chronically online population in history is making sense of the race.

The times continue to be unprecedented. Especially when choosing this next U.S. president.

Candidates popping up on Twitch live streams. Speech sound bites extracted and remixed for trending TikTok audio minutes after they air. Coconut trees and cackle fan cams and ear bandage costumes. Super PAC founders enticing voters with millions just to register and candidates taking conspiracy theories all the way to national stages. Yes, those are all true statements of true things that have transpired in this race so far, online and irl.

Heading into Election Day 2024, Ever Mack, an elections researcher working on the digital analysis unit at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, has been tracking the most chronically online population in history to make sense of Kamala Harris, Donald Trump and the lawful, chaotic good/evil that is this dog and pony show. In a world where media saturation is constantly reaching new peaks, Mack says disinformation has driven the discourse this election season faster than ever before.

“We see foreign state actors doing it. We see individuals who have like monetary interests doing it,” she says. “There's a lot of different people who contribute to the disinformation ecosystem. But because we are constantly online, and we're constantly taking in information, a lot of times, our own checks and balances systems don't keep up. And so that's kind of where I come in, checking to see where these narratives are most prominent, what things are really catching fire, and how we can inoculate against some of them.”

Mack, who joined ISD in 2024 after working as a voter protection manager on Stacey Abrams’ campaign in 2022’s midterm elections, specifically monitors political mis- and disinformation and extremism in the digital sphere. In addition to her day job, Mack works as a freelance makeup artist and creates voter awareness content by interviewing members of the millennial and Gen Z voting public for her own vox pop series, Pretty Girl Politics.

Beyond being recent buzzwords, the difference between the two forms of messaging comes down to motive. Misinformation, as Mack describes, is an accidental way that false information can be disseminated, usually through people sharing information socially that they haven’t fact-checked to be true. “Disinformation is a lot more targeted,” Mack says, explaining its the intentional dissemination of false narratives.

“The way disinformation works is that it kind of wears you down,” Mack says. “So, like, the first thing that you see that's false, you're like, ‘No, that's not real.’ But then the 20th thing that you see after seeing it over and over again, or different iterations of it, it kind of wears your brain down. It's the same way that people talk about manifesting – which, I love when there's overlap over my girlie pop ways and my research – but when people are talking about the things that you say, the things that you see all the time, it registers and that becomes your reality. The narratives that we ingest constantly, they create a foundation to where our brain goes.”

In an exclusive sub_stance interview, Mack surveys the most pressing issues for voters this year when it comes to political disdain, media literacy, voter suppression and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SM: How has mis- and disinformation changed this year? How are you seeing the effects of disinformation play out in this race specifically compared to U.S. election cycles of the past?

EM: Disinformation is so problematic because it puts everyone at a disadvantage. I think that disinformation and bad actors who use it to get to an end goal often exploit the fact that people are upset, right? A lot of people are not happy with the political system as is, and it's understandable. There's a lot of things to have gripes with. But when we operate from a place where our information isn't accurate, it makes it so that people are operating from not a free speech environment. This is a curated speech environment, and that's what people lose sight of.

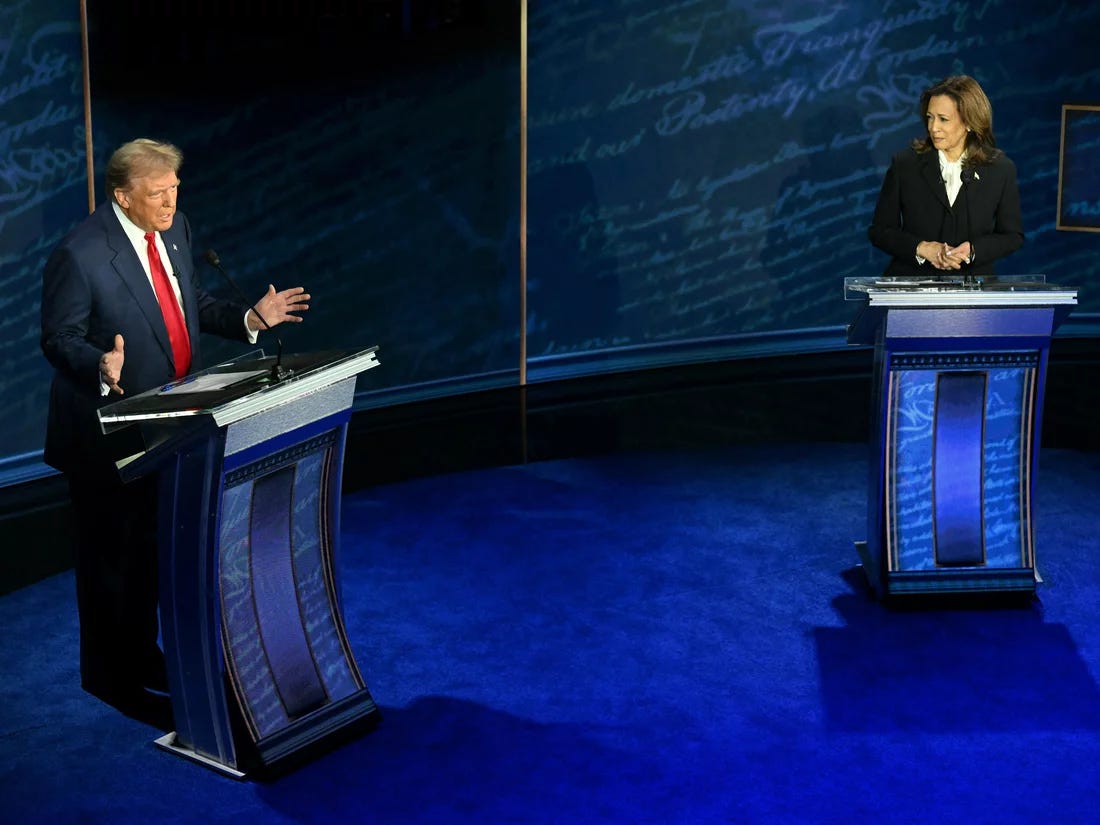

I think that in this race, the narrative about Haitian immigrants in Springfield eating cats was insane to watch. And as somebody who works in a space, see how it literally, just like, got bigger and bigger and bigger, to the point of it being mentioned [at a presidential debate] despite people coming out and saying that these things are baseless, right? But it's because there's people, individuals who have credibility, because they have large stages and they use their platforms and say these things, and they’re real life impacts on these individuals.

“When we operate from a place where our information isn't accurate, it makes it so that people are operating from not a free speech environment. This is a curated speech environment, and that's what people lose sight of.”

And so I think that number one, I want everyone to take a pause. I think that's the best thing that you could do when you come into contact with new information, especially when it's sensationalized. There's a lot of things that are clickbait. A lot of things are a crazy headline to get people to engage for a moment because right now, attention is currency. And then, it can become a trend, and basically a joke, right?

And so, people aren't caring about the real-life impact on individuals.

I think the biggest example of it was January 6th. We see this capital insurrection, because people are mobilized at this idea that our elections are fraudulent, which at its core, like, debases this ability of our democracy. Literally, that is the reason why I do the work that I do to help us all, like lock in, because at the end of the day, again, everybody, the foundation of democracy is everybody having different opinions and us through a diplomatic lens, figuring out how we can make our nation work for us as a very diverse collective. But if people don't believe in that, then what do we have? And so I think that as we continue to have these narratives pushed at us, we really have to make sure that we are being conscious in the things that we share within our own communities, and like being mindful of what the end goal of these bad actors are.

SM: But especially with AI now, they're being dispersed and presented more convincingly and rationally, to the point where, they're being marketed well, so it's getting harder to even decipher what it is and isn’t conspiracy.

EM: Exactly, I think that's why we have to understand that number one, nobody is immune to it. I love my parents and they are relatively speaking, very media literate. And I still have to tell my dad. He's on LinkedIn and he'll send little posts that he'll see on LinkedIn, like, ‘Did you see this?’ I'm like, ‘Daddy? Did you check your sources?’ And these are people who I come from a background where both my parents were detectives. So these are people who operate from experience where they are very critical of the information they receive. And still, it's very easy to fall into these pitfalls.

We all need to be diligent… We need to get to a place where we are reading things and the same way that, like, we see an ad or a commercial, and there's like, a level of, ‘Okay, they're trying to sell me something when you're on these platforms.’

SM: Related to disinformation and certain narratives becoming more popular, do you feel that there is a divestment in the very idea of democracy and the democratic process from 2020 until now?

EM: This is less from my like research, and more so just from conversations and some of the content that I'd made, like interviewing people. I do think that there is a divestment in the American political system. And I think that 2020, itself, was like a hemorrhaging event, in a sense. It was so different than anything anybody had experienced in modern history, and I think that it caused a pause in normalcy and like the buy-in on what the everyday we had established. I think that there are major political events taking place in the world right now which have either made people check in as far as, ‘I hate what's going on right now,’ or check out as far as, ‘I can't believe this is happening and nothing is changing.’

And I think that especially for younger people, it is a very hard time, especially when you, like, grew up with Obama, and then you see Trump, and then you have Biden. And you have all these eras where you have all of these instances where people are like, promise change, and then they don't necessarily feel change. When you are not a political person by nature, which most people are not … if you don't have the capacity to – because being politically aware, in a lot of ways, is a privilege and I don't think people talk about that enough. You have to have the capacity to be conscious, and if you are constantly trying to survive or you're trying to provide for your family, that's just not going to register as a need for you. But I think all of those things combined have gotten some people to a place where it's like, ‘I don't know if it matters.’ Especially people of color, who have historically been disenfranchised in this country, and then they see this country not only continue to disenfranchise people here, but go overseas and do things that they don't agree with, and continue to pay tax dollars.

I think that a lot of the feelings are valid, but I think that we all come to different conclusions. Because when I interview people and they tell me that they're not voting, I've not heard a reason where I don't understand where they're coming from. But I think the end goal I disagree with. I was at Culture Con, somebody said – I thought it was such a good statement – she said, ‘I am not going to give up any level of power to a country that owes my ancestors and like has not paid them back, owes them a debt and has not repaid it yet.’

My whole ethos with my politics is based in an understanding of Black history and understanding that like, my grandma beat into me, like, ‘You're gonna understand where you come from, You're gonna understand how hard it was for you to be able to participate civically and be invested in this country.’ And for that, I value my ability to vote. And don't get me wrong, I don't think that voting itself is the thing that changes everything, but I think that not voting takes away a level of power which I am not willing to give up.

SM: You’ve been surveying people at Culture Con, I know you were at Howard Homecoming, too, interviewing people. What are the policies that voters you ask are closely focusing on and how does that compare to election cycles past?

EM: Especially at Howard, my classmates were around ranging from like the 20 to like 25, a lot of those individuals who I interviewed. The good thing is that interviewing them showed that especially the Black community, is not a monolith, just like no community is a monolith. And I think that there was a range of things that they were concerned with. I think one of the main things, overwhelmingly, was reproductive rights. And I think that that is reflective of just a general sentiment that people do not want to feel like the government is overstepping as far as their bodily autonomy my classmates were around like ranging from like the 20 like one to 25 a lot of those individuals who I interviewed, I think the good thing is that interviewing them showed that especially the Black community, is not a monolith, and no community is a monolith. There was a range of things that they were concerned with. And I think that that is reflective of just a general sentiment that people do not want to feel like the government is overstepping as far as their bodily autonomy. Reproductive rights was something that I saw from women and men, different ages, that was inconsistent, and that was from Culture Con, from Afropunk, all these different events, reproductive rights was definitely at the top of people's lists.

I think that another thing is definitely the economy. Especially at Howard, where my contemporaries are, like early career professionals, people who are looking to buy homes in the like shorter term, with the cost of living, with mortgage rates right now, I think that it is feeling very, very not feasible. And in a country that requires you to pay taxes in a country that you want to, like build in, that is a frustrating point.

I also know that foreign policy is a very big deal. And I know that foreign policy has become a bigger deal this election than it has in the past two cycles. I think that a lot of people are not happy with what they're seeing taking place overseas, and I think that it will motivate individuals one way or another. Now I don't know how that's going to land, because at the same time, I don't know that the people who are running currently are reflective of the goals that a lot of people who are expressing their frustrations with want to see. So, I'm interested to see how that impacts as far as turnout. Because the other thing is, I think a lot of the things that the people are concerned with right now and what's motivating people to turn out is moreso harm reduction than an idealized world. I think that that is where we're operating from right now as voters. I’m very interested to see how that transpires as we get closer.

SM: Do you think there’s a connection between Kamala Harris being a Black woman and strategically, in terms of marketing, downplaying her gender this time around, and Black men voters being put under a microscope as a demographic this election?

EM: This is something that I will say, the whole racial categorization of Kamala Harris, to me, has been very funny to watch. As a Black woman who went to Howard, my mom is an AKA, there's a lot of overlap for me to, like, at no point have questioned Kamala Harris's racial identity. I think because they make race such a big thing and there have been, like, outspoken videos of, like, some Black men saying she’s not, and that became a whole conversation within the Black community of whether or not she's Black and whether or not like her racial identity is valid. I think that that definitely plays a role, especially because I feel like compared, and this is just like what I've seen online, I've seen Black men being outspoken, like, ‘She's not Black. She's not this. She's not that.’ I think that that's just a silly point, honestly, and it makes me frustrated sometimes, because I feel like the way our discourse goes, we harp on things that don't matter as much. And it takes away from the real, valid questions that people should be asking.

I think that everybody should be critical of our candidates. I think that being critical of our candidates is a hallmark of a good democracy. I think if we look at anybody and say she's black, I'm going to vote for her. That's problematic, inherently. But I do think that then making it a talking point to say, ‘Well, she's not Black,’ and then jumping to, ‘Well, Black men are not voting, or Black men are not doing this, or they're going to be the decision makers.’ It makes it a very racialized view of things.

Also, every time we have a Black candidate, it kind of seems like their race their identity [comes] into question. With Obama, it was birtherism, and now it's ‘She's not Black,’ even though she's consistently participated in the Black community and Black culture. I want us all to, like, really ask better questions about our candidates, because at the end of the day, whether she's Black or not, if she is the president, then you need to be more aware of what her policies are, and not whether or not her grandma is actually Jamaican and if a picture is real.

SM: Right, because that's the disinformation, and like, the use of disinformation as distraction. So, compared to the, the excitement around Obama as the first Black man president in 2008, what is the difference you're seeing in your research about the prospect of Harris being the first Black woman to hold office? Are there any gendered opinions coming through in your research?

EM: I definitely think that there's a level of excitement at the prospect of having both a first Black woman female president, and a first Asian-American female president, because she's both. You can be both in this country. And it would be really crazy of me not to acknowledge the fact that as a woman, she faces a level of misogyny that I think made that Obama didn't have to deal with. Obama was this cultural figure in a lot of ways, people galvanized behind him because he represented change. I think that a lot of the more extreme political iterations we've seen since then have kind of been a response to Obama, because Obama became president in a country where he wasn't supposed to become president, just by how the country was founded. And so a lot of people were kind of thrown off, you know? And so now we're facing this horizon where not only might we have another brown, Black president, but it's also a woman, and that is really scary for people whose foundational ideologies are there's certain groups that are better and there's certain groups that are smarter, there's certain groups that need to retain the power. And so, I think that her existence makes people uncomfortable, and I think it's reflected in the narratives. I unfortunately have the ability to see some of what the worst is said about her, and it's literally just racism and misogyny. And I think that that is reflective of some of the worst parts of our society, which are reality. At the same time, I see people who are so excited and even just, I think, no matter who you support. If you're a Black woman in politics, it's cool to see somebody reach that level who looks like you, because we've not seen it before. So you get both ends of the spectrum. But I definitely think that it's a confronting moment for everyone, because it's not something that we've seen before.

SM: There’s also been a lot of critiques that call into question Harris’ capability as she’s started to campaign. I’ve definitely seen some people lean on recency bias and compare her and Trump’s credentials to say he’s more fit because he’s ‘done the job before.’ But I wonder, is it a different level of public consciousness that we're in right now? Is it because of what you're mentioning before about her not explicitly, denouncing the acts of violence by Israel and saying she won't change Biden's Israel policies? Is it her marketing? Is it that we could be more susceptible to disinformation about a woman?

EM: I think we're dealing with a combination, because it's like an ecosystem of all these different things, right? We were dealing with, yes, disinformation, yes, misogyny, yes, gripes about our foreign policy, yes. There's so many different aspects that contribute to it. I do think that the level of scrutiny that she faces is consistent with the level of scrutiny Black women face in public spaces. And I think that it is really hard for me to come into contact with all these different narratives, come into contact with all the things that I'm seeing about her and just totally disregard the fact that Black women in general are all are held to a different standard we have to overachieve. Even like the conversation about qualifications, I think that if you were to look at a paper and compare both candidates, if you really like, take away names and say that she is not the qualified candidate, or a qualified candidate to be in the race, I think that you have to be operating from some predisposed bias somewhere, because just on paper, like the attributes alone, I don't think that the conversation should be, ‘Is she qualified?’

SM: One thing I think about working professionally in the music and culture space is the social construct of celebrity. How have you seen the celebrity endorsement change in terms of its influence over the years? How much influence does it hold with voters in this race?

EM: It's kind of, it's like a two part thing, because, again, it depends on the voter, right? I think for people who have no political investment, but really love Taylor Swift. If Taylor Swift says, vote for this one person, and they again, have no care, have no awareness, then that might be the motivating factor.

Especially with the whole play on using rappers and going to things, are capitalizing on the fact that, again, the vast majority of people don't really care about politics, especially not on a sustained level. So if the person that they look up to, who they do have a vested interest in, takes a stance and says, ‘Well, I support this person. How could you not support this person?’ I would hope that that's not the mobilizing thing, but the reality of what a lot of influences in this world is it might be. And so I think that I've seen conversations where people are tired of it. I've seen conversations where people who are more politically inclined have critiqued the influx of celebrity into the political engine.

SM: Which are you seeing more of right now?

EM: I feel like I probably see more people who are following the people that they support and get behind them. But I say that because I think the people who take the time to speak out about it are inherently going to be fewer and farther between. I think it's much easier to support somebody and be like, ‘Yeah, I go with Amber Rose when she goes to RNC because I love her and I love what she does.’ And I get it. I think it takes more time and more effort to be outspoken and say, ‘Hey guys, maybe we shouldn't take our policy advice from somebody who's never been in politics before.’ some, you know, like it takes more effort to go against the granite in that sense. And I think that so much of our culture is celebrity driven, so much of our culture is influenced by influence that's just kind of like, again, attention is a currency. That’s more my perception of things.

SM: What are some of the most extremist theories that you are seeing gain steam right now in these last couple weeks?

EM: One that I am really concerned with is this non-citizen voting theme, and I think that that is particularly scary to me because I do Spanish language monitoring as well, and so I watch conversations taking place in Latino communities, and I also watch things that are targeting those communities.

So, it's my research, and then it's also my lived experience of having conversations with people, because I'm the annoying friend that if I'm out, we're probably going to end up talking about politics at some point. And I have friends, especially working in the fashion space to have a spectrum of political ideologies and come from a variety of places. And I've had more than one conversation that has been very concerning to me. I know that they don't necessarily perceive them as being xenophobic in nature, but they [are] xenophobic. And the thing about a lot of these narratives, and why they gain steam is because a good conspiracy theory, a good narrative, has a basis in the truth and plays on somebody's predisposed belief and pre-existing concern.

So, let's say people are concerned because they pay a whole bunch of taxes. The schooling systems are bad. They can't get access to like government assistance. And then the perception is illegal aliens are coming and they're taking all the resources, and they're able to do all these things right now. What the reality is is the way that government funding and allocation happen. It doesn't. They're not counterintuitive to one another, so, but people don't know that, and so there's a baseline perception.

Then you have public figures saying, ‘Yeah, and then, you know, they're bringing all these illegal aliens, and they're taking all the resources, and they're bussing them in to steal the election. And you know what's so crazy? They're gonna do that, and then you're not gonna have a democracy. Then all your rights are gone.’ And when you have somebody who already has a baseline frustration of something that's valid, where they're not getting the resources that they need from their government, right, and then you build on it, like, ‘Oh yeah, I do see, like, a lot more new people around, and somehow they're able to go to this school, and somehow they're able to get government assistance.’ And then this person, who's a public figure who has a platform, then says, ‘It's intentional. Matter of fact, they're all here because they're trying to steal democracy and take away everything that you you know.’ That it is literally like the foundation of any type of, like, good conspiracy theory, bad actor narrative. But that one, particularly, I feel like has been increasingly prevalent. I've seen people, especially in the black community, espouse, like, anti immigrant narratives. And I think what we've seen with the Springfield thing is kind of an offshoot of that, because that is anti-immigrant inherently.

Have you ever watched The Boys?

SM: Yeah.

EM: There’s a new character, she's one of the newest additions, she's like the very conservative. In this episode, and I thought this was ingenious, because she was like, ‘People are lonely, and I give them something to believe in.’ And I promise you a lot of these bad actors operate from the same place.

I think that at the baseline, and this, again, is like part of my ethos of politics. Everybody wants to just live an OK life. Everyone wants to be able to, like, provide for their family, not have to worry about their safety. Like there's very baseline things that universally human beings have an interest in. And I think that our politics have gotten to a place where it factionalizes us to really dehumanize the baseline universal interest of human beings, of Americans.

“I think that our politics have gotten to a place where it factionalizes us to really dehumanize the baseline universal interest of human beings, of Americans.”

The same way that she harped on the fact that people and we in a loneliness epidemic like that is something that has been established. Yeah, we have social media, so we have like, this weird para-social thing where we're hyper connected, but at the same time, a lot of us lack meaningful relationships. And so when you have people who are lacking meaningful relationships, lacking community, lacking resources, lacking purpose, it's a vacuum, and it's an opportunity for bad actors to exploit that emptiness: ‘Because you don't have any of those things. I can tell you why you don't have those things. I can tell you why you're lonely, and I can tell you who's to blame exactly, and I can tell you exactly who's to blame. And if you come with me, we can all fight this together. So much of the rhetoric that I see is we are freedom fighters. We are, we're patriots.’

To be honest, it takes a lot of time to be on the far end of extremism. It takes a lot of time to be on your computer all day and say all these conspiracy theories, to organize and do all of these things that are anti-democratic. [Extremism] takes a lot of effort. But people who lack community, people who lack an outside identity, all these things, have the time and capacity to do that and it gives them a level of fulfillment.

SM: But in The Boys example, which I agree, is such a great example, but The Boys is just so outlandish and satirical and sensational with it that it's written off in the show as just kooky propaganda. But in the spaces you're working in, it's all promoted and marketed as ideological and very logical. So then, what's the difference between disinformation and just straight-up propaganda?

EM: Honestly, there's not that much of a difference. I think disinformation is propaganda. I think disinformation is just, they're like targeted campaigns. But an offense, propaganda is just us saying things to promote a certain political ideology. Anything could be propaganda, anything that promotes a level of extremism to one way or another, to say that this is something, I think that it's kind of almost like semantics in a sense. I think that disinformation, for me, functionally, is helpful, because sometimes it's a part of the conversation with misinformation, right? And when people don't know that they're spreading this or misinformation, it helps them not feel so like othered for doing so, because a lot of like, people don't know. If your auntie's sharing what she has in, like, the WhatsApp group chat, she's not trying to end democracy, she's trying to spread knowledge, right? And so, it's a lot easier for me to say, ‘You're spreading disinformation right now,’ then, ‘You're spreading propaganda.’ I think that that is, for me, at least, the distinction. But I do think that a lot of the disinformation that we see is effectively propaganda.

SM: I have a lot of friends from different cultural backgrounds who grew up outside of the US, and grew up in Nigeria, grew up in Haiti, and it's funny because, for them, there is a unified nationalism in knowing that your government is corrupt and then not hiding that it's corrupt. And they'd be like, ‘Yeah, it's straight-up propaganda. And we call it that, like, we call a spade a spade, right quick.’

I think that is part of the basis of so much dissent in our political sphere and our political practice, because of how this is 100% a nation that is ideologically diverse. It's people living very different lives. You travel from state to state, and their lived experience is vastly different, compounded with the fact that there's so much racial diversity and racial inequality built into the DNA, and like the fabric of the country, so is, political dissent, on a spectrum of like disagreement to utter chaos, is that kind of just the fate of the US democratic process no matter what?

EM: That's a really good question. I think that it's hard. I think about that often literally, because as somebody who chooses to participate in our democracy, and obviously it's not governmental, but to try and protect it, right? I believe in democracy. I believe in trying to make the systems that we have already as good as possible with what we have right because that's what we have right now. I think that political dissent is necessary for democracy. I think having people be outspoken is necessary. I literally just think that we need some decorum. I think that, like, there is space for us to talk about our gripes. Because, don't get me wrong, as somebody who is well-versed in African American history, in how this country disenfranchised us, if we didn't have political dissent, I would not be here talking to you right now. You know what I mean? Like, if we didn't have political dissent, I would be in a very bad situation. So, I think for me to say anything, but I'm a supporter of political dissent, would be kind of crazy. I think political dissent drives us to be better.

I think its that and we can't lose our minds. There's a lot that makes you really angry about this country. I think the more you learn, it creates more frustration. So I get all of that, and that's why, again, I think that so many people have, like a universal agreement on certain things, and we just end up on different places, end up in different ways to like, ‘Okay, I I think that this is wrong. I'm gonna vote.’ Or ‘I think this is wrong. I'm not gonna participate.’ Or, ‘I think this is wrong. I'm never gonna talk about politics, and I actually don't want you to be in my face right now.’ I think that we have to hold dissent as a space, but at the same time, it can't be January 6 because you're not happy with who won and is president. I think that as the whole function of democracy is we have a system, and if we are committed to being a country and having investment in the system. We have to stand by the system, even if the results of the election are not something that you're happy with.

SM: Heading into the final stretch into Nov. 5, what are the pockets of discourse you’re going to be monitoring most?

EM: Well, because I dealt with it in Georgia, I'm hoping I don't hear a whole bunch of stuff about the voting machines. I really do. There's just so many, like, small pockets of, like, disinformation and things that have, like, been proven over and over again that aren't the case. And I'll be honest, like some of the top points are a little bit newer. I know that, like post-Hurricane Helene, that's like a big thing with North Carolina especially, and I feel so bad for those communities that have been done stated and in Florida with Hurricane Milton, and that is like a whole other tangent of things. But because of the chaos that is caused in those communities, I know election administration has been changed, and there's already been so many conspiracy theories around that I just I know that the local boards of elections, the state boards of elections, have been working to, like, maintain secure Board election administration in those areas, I see small pockets of individuals who've already started saying that, you know, it's not a fair election already.

So, those are the things that I'm concerned with. And again, if you look at the facts, if you look at the things that people are doing, if you look at the actual rate of non-citizens like being registered to vote, all of those things help negate those narratives, but a lot of people don't do the work to like, go beyond the headline that they see, go beyond the tweet that they see, go or the X post that they see, go beyond all of these things. Those are the things that I'm being mindful of going into the election.

Not IRL

I’ve been too busy to consume every cultural nugget I want, but here’s a rundown of what else is setting this year’s election discourse apart:

Pew Research Center is monitoring people’s anxiety levels around the transition of power after this election and it’s looking a lil shaky warrior.

NYT pointed out the feminist blogosphere of 2016 that galvanized and contextualized Hillary is all but gone in 2024. Are we better off…without it? (Jezebel forever! ijs)

Tangentially related but echoing heavy to the tune of bodily autonomy rn, Doreen St. Felix at The New Yorker literally body’ed this piece about how racialized waistlines have mixed up a new flavor of panic, dysmorphia and impending Met Gala microaggressions.